Uneven Recovery in Latin America: A Regional Overview

2015.07.02

The recent slump in oil and commodity prices has somewhat choked Latin America’s growth prospects as a natural resource-rich region. Not every Latin American country has responded in the same way to the slowdown. Each has chosen a development path dependent upon their natural resource endowments, but a majority has turned to diversification of industry and exports for growth. Moves such as the expanding Pacific Alliance and the normalisation of US-Cuba relations show how Latin America is gearing towards continued market liberalisation, while the expansion work on the Panama Canal demonstrates an investment commitment to trade-related infrastructure.

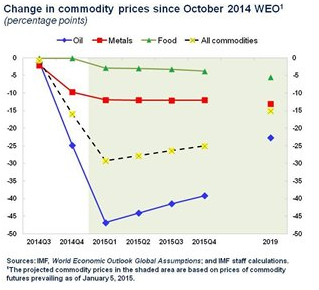

Nosediving Oil and Commodity Prices

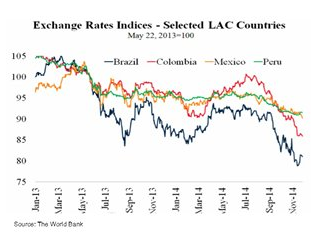

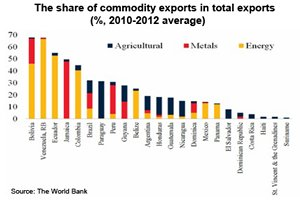

Since the second half of 2014, tumbling oil and commodity prices and the resultant depreciating currencies have battered most of the world’s natural resource-rich countries, Latin America included, dulling the region’s shine for exporters and investors that has been built over the past decade. Nevertheless, the impact of the price nosedive is clearly not the same across the board. Some countries less dependent on oil and commodity prices are poised to outperform those which are more dependent, but the situation becomes much more complicated when other regional settings or characteristics are also taken into consideration.

The plunge in commodity prices and currency depreciation

Take oil as an example. While Colombia, Brazil, Bolivia and Panama are big energy exporters, most Latin American countries are in fact net oil importers. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in 2014 only Venezuela (with net oil exports representing more than 30% of its GDP), Ecuador (less than 10%), Colombia (less than 10%), Trinidad and Tobago (less than 10%) and Mexico (close to balance) were net oil exporters in Latin America.

This truth, however, does not necessarily mean that those countries with big oil import bills are automatically beneficiaries of the recent price plunge. Quite a number of them have long relied on subsidised oil deliveries from Venezuela under the Petrocaribe [1] agreement. With Venezuela experiencing growing economic strains (it is expecting a 7% GDP contraction in 2015), its Petrocaribe support to other countries has been diminishing. While lower international market prices for oil should be sufficient to compensate for the potential loss of subsidised oil supplies for most recipients, some governments may experience short-term fiscal pressures.

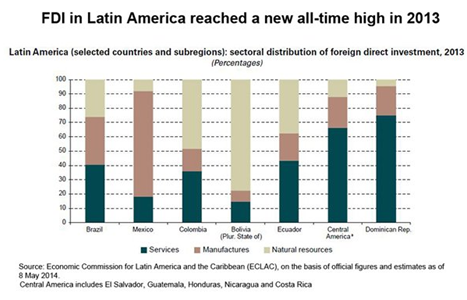

On top of export business, the free fall of oil and commodity prices has also triggered a retreat of foreign direct investment (FDI) from Latin America. FDI is estimated to have slowed down in 2014, after reaching a new all-time high of US$188 billion (+6% over 2012) in 2013. While the economic upheaval in Europe is contributing to the retreat, the confirmed fear of an economic slowdown in China, the world’s second largest economy, is definitely a more major cause. With an estimated 70% of China’s imports from Latin America being commodity-related and nearly 90% of China’s outbound direct investment (ODI) in Latin America being associated with natural resources, the slowdown of industrial activity on the mainland will have an impact on the region’s FDI receipts.

Over the longer run, the weakness in oil and commodity prices would undermine the prospective potential of developing the region’s natural resources. In turn this would impair the process of channeling oil or commodity windfalls into other economic sectors for the purpose of industrial, export and economic diversification in many Latin American countries. Nations in the South, Central and Caribbean, and North of the region have different natural resource endowments, industrial strengths and competitive edges, implying varying trade and investment prospects for Hong Kong exports and investors in the years ahead.

Uneven Economic Prospects

South America, benefitting little from the strong US recovery, has been facing stiff headwinds from a slowing global economy and the resultant decline in demand for exports of metals and agricultural commodities. The economic challenges are even more apparent from investment, which has slowed every year since 2010, and is forecast to decline in 2015. Beyond the impact of worsening external conditions, a variety of domestic issues are also at play.

As Hong Kong’s largest trading partner and import source in Latin America, Brazil’s private sector confidence remains tepid in light of the lingering political crisis surrounding President Dilma and her government’s inability to pass economic reforms to address the enormous economic challenges. Gaining little stimulus from hosting the 2014 FIFA World Cup, Brazil’s economic activity has been anaemic, with growth rates falling sharply from 3.9% in 2011 to 1.8% in 2012, 2.7% in 2013 and 0.1% in 2014. Even in light of the positive impacts of hosting the 2016 Summer Olympics – South America’s first Olympic Games – and the government’s renewed commitment to uphold fiscal discipline and curb inflation, Brazil’s economy is forecast to see a 1% decline in 2015, before showing positive growth in the Olympics year.

Despite some easing of the exchange rate debacle and a better-than-expected growth outturn (+0.5%) in 2014, Argentina is expected to continue to struggle with large macroeconomic imbalances. Capital flight and high demand for greenbacks in a bid to offload the depreciating peso have made the blue or parallel exchange rates steadily stay some 50% above the white or official rate announced by the central bank. The resultant exchange rate risks and persistent shortage of US dollars have made international trade very challenging for Argentinian companies, not to mention the wide array of protectionist measures and domestic-oriented development directions. Against this backdrop, the latest IMF forecast expects Argentina to see a 0.3% GDP contraction in 2015, before returning to a pasty 0.1% growth in 2016.

Growth prospects for Chile, Hong Kong’s second-largest trading partner in South America, are relatively more favourable, though pared back since commodity prices plunged in the last quarter of 2014 and following a setback in investment in various mining projects. Implementation of various reform programmes set forth by President Bachelet – notably the tax reform which gradually increases the corporate income tax rate from 20% before 2014 to as high as 27% in 2018 published 29 September 2014 in the Chilean Official Gazette – will likely come to fruition. To stimulate the economy, the Chilean government, has budgeted for a 9.8% surge in public spending for 2015, using the extra corporate tax proceeds and authorisation to issue new debt to boost investment in education and healthcare. In the private sector, banks have resumed their easing cycle, with key interest rates such as the interbank rates (or monetary police rates, MPRs) edging down to 3% since November 2014.

Meanwhile, Colombia and Peru will continue to demonstrate resilience despite the global oil/commodity price turbulence and the weak European economy. This resilience comes from their relatively sizeable populations and continued efforts to promote diversification in both export category (away from traditional items such as metals and primary agricultural products to non-traditional exports involving higher technology content and higher value-added) and export destinations (a tilt towards the burgeoning Asian market).

As for Central America and the Caribbean, cheaper oil prices plus the robust US recovery are important driving forces for the growth of exports and tourism and economic development, along with the stiff challenges stemming from the reduction of oil supplies under preferential financing terms from Venezuela. Remittances and tourism receipts are expected to continue to fare well in 2015 and the years ahead, while stronger exports to the US will likely underpin domestic activity further.

Panama enjoyed the fastest growth in Latin America between 2011 and 2013. It is poised to remain sturdy and, with a projected 6.1% growth in 2015, will regain its crown as the region’s fastest-growing country from 2014’s title-holder, the Dominican Republic. As a major all-water trade route between Asia and the Gulf of Mexico or the East Coast of the US, the long-awaited completion of the Panama Canal expansion work by 2016 is projected to exert significant impact on the flow of freight between Asia and the US. This, coupled with the ongoing expansion of the Colón Free Zone (CFZ) and Panama Pacifico Special Economic Area (PPSEA), is set to strengthen the country’s unrivalled position in global logistics, while lending support to its trade diversification (or reducing dependence on the Venezuelan and Colombian markets) and investment promotion efforts.

Also noteworthy is Costa Rica, whose export basket has drastically changed over the past decade from traditional items such as fruit, vegetables and textiles to high-tech items such as integrated circuits (ICs), computer parts and components and medical equipment. High-tech products are estimated to have surpassed the 50% threshold of Costa Rican exports. This explains Hong Kong’s big import bill from the country, while highlighting another tranche of trade opportunities for Hong Kong companies with Latin American countries.

Mexico, Hong Kong’s Number One export market and second-largest trading partner in Latin America, is projected to edge up from 1.4% growth in 2013 and 2.1% in 2014 to 3.0% in 2015, thanks to the positive spillovers from the stronger US recovery. The country, as a (marginal) net oil exporter, is supposed to be vulnerable to the recent oil price fall. It has, however, secured its 2015 oil revenue through financial hedging. This gives an extra reason for businesspeople to feel confident about the economy of the world’s largest Spanish-speaking country.

Major Developments in Latin America

Near-term prospects aside, Latin America has seen a few interesting developments. In addition to the long-awaited expansion of the Panama Canal, these include the dynamically growing Pacific Alliance trade bloc and the restoration of diplomatic relations between the US and Cuba.

Pacific Alliance: A Fast-growing Trade Bloc

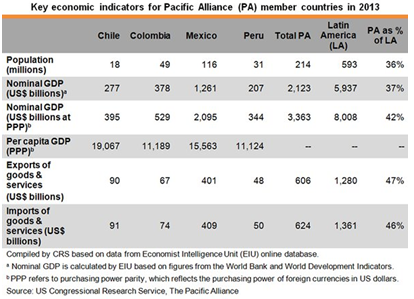

In a bid to have better synergy when making inroads into the Asian market, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru officially established the Pacific Alliance (PA) in a framework agreement on 6 June 2012. This created a Latin American bloc of 214 million consumers and a combined annual output of more than US$2 trillion. Today, the PA has 32 observer countries including Australia, Belgium, Canada, China, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Finland, France, Germany, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Israel, Italy, Japan, Morocco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Paraguay, Portugal, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, the UK, the US and Uruguay, while Panama and Costa Rica are in the process of becoming full members.

Representing more than one-third of Latin America’s population and GDP, and nearly half of its foreign trade and foreign direct investment (US$85 billion in 2013), the PA is widely considered to be the first major free-trade initiative in Latin America since the creation of the Southern Common Market (Mercosur) in 1991. With the deeper regional integration, the four member countries aim to go far beyond the free flow of goods, services, capital and labour among themselves, and strengthen ties primarily with the Asia-Pacific region.

In addition to the immediate elimination of 92% of tariffs between the four member countries (the remaining 8% will be phased out in seven years) upon the signing of the Additional Protocol of the Framework Agreement for the Pacific Alliance on 10 February 2014, the PA has also taken numerous steps to embrace its ambitious agenda. For example, it has eliminated visa requirements (e.g. Mexico eliminated visas for Colombians and Peruvians for stays of up to 180 days on 17 November 2012); has integrated their financial markets (e.g. the Mexican Stock Exchange (BMV) was connected, in December 2014, to the Latin American Integrated Market (MILA), which was formed by integrating the stock exchanges of Chile, Colombia, and Peru in 2011); has carried out joint promotion for exports, tourism and foreign direct investment; and has either shared facilities or opened joint embassies/consulates around the world.

The PA’s concerted liberalisation efforts do not automatically create a free-trade area for Hong Kong exports, given the relevant rules of origin. But the Sino-Chile, Sino-Peru and Hong Kong-Chile free trade agreements – and tax treaties such as the comprehensive double taxation agreement between Hong Kong and Mexico – mean the city could play a pivotal role in taking the already-buoyant trade and investment between Asia, particularly the Chinese mainland, and Latin American countries on the Pacific Rim to a new, higher level. As the world’s freest economy, a major international financial centre and the most important window of Chinese outbound direct investment, Hong Kong makes a reliable partner as PA members reach out to Asia’s consumers and investors.

On the other hand, Hong Kong businesspeople can gain an easier, bigger access to the distant Americas market via the PA. For example, by partnering with a Mexican manufacturer and complying with the relevant local content requirements, the jointly produced merchandise (which then becomes “made in Mexico”) can be sold tariff-free among the four PA countries. This can be further extended to other markets in the region as the PA expands over time to incorporate new members or signs new plurilateral trade agreements.

The Normalisation of US-Cuba Relations

Since severing diplomatic relations in 1961, a stifling Cold War-era trade blockade has isolated Cuba from the US until recently, when the two countries began the normalisationprocess. In December 2014, US President Obama announced the most proactive policy shift towards Cuba, with the re-establishment of full diplomatic relations. In conjunction with the historic interaction between President Obama and Cuban President Raúl Castro at the Summit of the Americas in Panama in April 2015, President Obama notified the US Congress on 14 April 2015 that he intended to remove Cuba from the list of state sponsors of terrorism.

While the ultimate decision to lift the embargo against Cuba is still in the offing, a clear regulatory change has been taking place in the normalisation efforts. In January 2015, the US Department of Commerce’s (DOC) Bureau of Industry and Security and the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control issued amended regulations related to licensing, inspections, investigations and penalties, which effectively relaxed the embargo with regards to air and sea travel, telecommunications, financial services and trade.

The normalisation of US-Cuba relations, and more importantly, the ultimate lifting of the long-lasting embargo will unleash the potential of the relatively virgin Cuban market. (1)

The normalisation of US-Cuba relations, and more importantly, the ultimate lifting of the long-lasting embargo will unleash the potential of the relatively virgin Cuban market. (2)

The 12 existing categories of authorised travel to Cuba previously required a specific Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) licence. But under the amended regulations, visits are allowed under a general licence and do not require a travel application. While this marks great progress in the relaxation efforts, charter flights remain the only way to fly from the US to Cuba. US-based carriers such as American Airlines, JetBlue and Sun Country currently offer charter flights to the island, with American Airlines operating roughly 20 flights a week from Tampa and Miami airports. All major US carriers have expressed interest in expanding flight operations and creating new routes to Cuba. No timeline has been announced, however, for when the US will officially announce a bilateral air transportation agreement with Cuba.

As for telecommunications and internet connectivity, further changes have been made recently to enhance the ability of Americans and Cubans to communicate with each other. Despite trade restrictions that limited US businesses from promoting private enterprise on the island, Cuba was linked into the GlobeNet submarine telecommunications cables in 2001. However, access is heavily limited by the Cuban government. But as the thaw in relations between the US and Cuba progresses, it will become increasingly difficult for the Cuban authorities to continue to limit telecommunications access.

The normalisation of US-Cuba relations, and more importantly, the ultimate lifting of the long-lasting embargo will unleash the potential of the relatively virgin Cuban market. (3)

The normalisation of US-Cuba relations, and more importantly, the ultimate lifting of the long-lasting embargo will unleash the potential of the relatively virgin Cuban market. (4)

These amended regulations also remove the spending restrictions imposed on US travellers to Cuba and will allow credit and debit transactions. However, financial institutions are not required to maintain or facilitate such transactions, and no US banks have officially announced that they will be opening branches on the island. However, American Express and MasterCard recently expressed significant interest in establishing payment facilitation and completion in Cuba. This may encourage other US banks and financial services companies to expand operations to the island. The amended regulations now allow US banks to establish corresponding accounts with Cuban banks, but Cuban banks are still restricted from doing the same in the US. The efforts of the large credit card companies support the amended regulations by allowing for the transfer of funds and issuance of remittances to Cuba. Despite this overall progress, US companies still face the hurdle of not being able to process and accept transactions from Cuban nationals.

As previously mentioned, the amended regulations maintain the prohibitions of doing business or investing in Cuba unless a specific licence is obtained from the OFAC. Although export licences are still generally required, under the revised regulations, new exceptions have been added. These enable the export and re-export of goods that “generally” provide support for the Cuban people in (i) improving living conditions and supporting independent economic activity, (ii) strengthening civil society and (iii) improving communications.

The DOC maintains the list of goods approved for export or re-export to Cuba, which currently includes a wide range of products such as building materials; equipment and tools for use by the private sector; items for use in scientific, archaeological, educational and sporting activities; and goods for use by news media personnel and US news bureaus. Similarly, since the year 2000 agricultural commodities, medical devices and medicines, and consumer communications devices have generally qualified as eligible exports not requiring a specific licence.

Only time will reveal the extent and pace at which the normalisation efforts will continue, however, the lifting of the embargo against Cuba remains within the purview of congressional action. Senate and House members from both parties have expressed many views since the historic December 2014 announcement. Through the introduction of nearly 27 bills, several congressional hearings and comments from influential members, the battle for normalisation seems to be only starting.

That said, Cuba has already seen an increasing number of foreign investors preparing themselves for the ultimate opening up of the market. For instance, China Harbour Engineering Company Ltd (CHEC), a subsidiary of China Communications Construction Company (CCCC), kicked off the construction of a new, multipurpose sea cargo terminal in Santiago de Cuba’s GuillermónMoncada Port (Cuba’s second-largest port after Mariel) on 13 January 2015, on the back of a US$120-million loan from the Chinese government. After the bay is dredged to a depth of 13.6 metres, the new terminal will be able to service sea vessels of up to 40,000 tons (up to 20,000 tons at present) upon completion in three years.

The normalisation of US diplomatic relations with Cuba is expected to have a relatively modest impact on Hong Kong. However, there is little doubt that sales of consumer goods to Cuba would increase if the US finally decides to end the trade embargo and allow US companies to export to Cuba without restrictions. The main reason for this is that US companies in the apparel, footwear, toy and game, household appliance and other sectors that make or source their goods from Hong Kong suppliers primarily for sale in the US market could begin exporting their products to Cuba, especially if they are already doing business in other Latin American countries.

Normalisation of relations could also result in a considerable influx of foreign investment into Cuba, especially in tourism and infrastructure-related activities. These could have a positive effect on sales of construction and related materials to Cuba. Moreover, the removal of financial, travel and other restrictions imposed by the US, in combination with the potential adoption of increasingly business-friendly policies by the Cuban government, could create a conducive environment for investors from all over the world, including Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland, to venture into the relatively virgin market of Cuba.

The Implications for Hong Kong

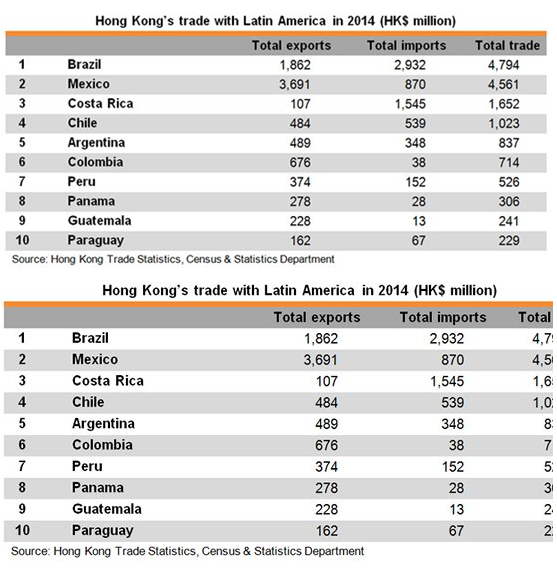

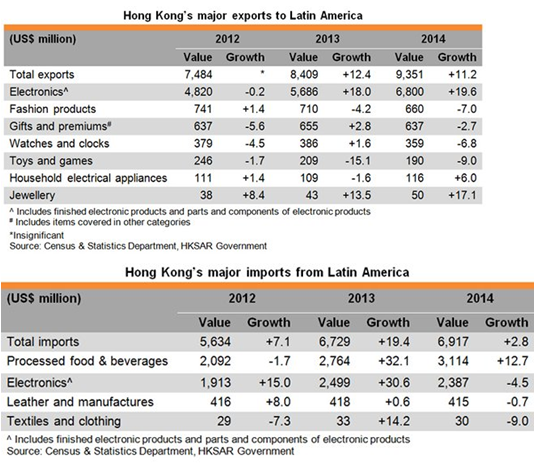

Latin America is the third-fastest growing region for Hong Kong’s external trade – up more than 90% between 2009 and 2014 – after the Middle East and Central and Eastern Europe. Exports and imports soared 124% and 59%, respectively, over the same period. However, in value terms, Latin America, with an annual trade volume of US$16.3 billion in 2014 (including the US$11.7 billion worth of Sino-Latin American trade conducted via Hong Kong [2]), still accounted for less than 2% of Hong Kong’s total trade. Aside from the tiny proportion, Hong Kong-Latin American trade has also been rather concentrated in terms of product category. For instance, electronics alone accounted for 73% of Hong Kong’s exports to Latin America in 2014, while processed food and beverages, electronics, and leather and manufactures represented altogether 86% of Hong Kong’s total imports from the region.

In the near term, weak global growth and the resultant slowdown in demand for oil and commodities will remain a major drag on the Latin American economy. Though the impacts may vary from country to country, the region’s recovery, if any, will show an uneven picture. Most resource-rich Latin American countries are striving to diversify their industry and exports, but some seem more successful than others.

By embracing free trade and pursuing continued market liberalisation, the expanding Pacific Alliance has been a role model of not only regional integration in Latin America, but of how a trade bloc with a free flow of goods, services, capital and labour can itself be an effective “going out” strategy. After surpassing the 40% threshold of the region’s total in 2014 and registering growth of nearly 150% between 2009 and 2014, Sino/Hong Kong trade with the PA will continue to thrive in coming years, along with the PA’s declared goal of expanding trade and economic ties with Asia.

The budding normalisation of US-Cuba relations and the imminent completion of the Panama Canal Expansion project are going to inject new impetus into the Latin American economy, engendering new possibilities for Hong Kong companies in terms of market, products, services, investment, and logistics, among many other aspects.

Source: hktdc

Visitor Registration

Visitor Registration Booth Application

Booth Application